Comprehensive Flood Risk Management for the Upper Mississippi?

Restoring Floodplains…With Science!

June 29, 2016Help Save Superman’s Home!

August 2, 2016By Olivia Dorothy, American Rivers

In August, the Mississippi River Commission will be conducting their low water inspection on the Upper Mississippi River and on August 11 will be holding an invitation-only roundtable to discuss flood risk management on the Upper Mississippi River.

Anyone who works on the Upper Mississippi River might ask, “Wait, didn’t we do a comprehensive flood risk management plan after the 1993 flood?”

President Bill Clinton surveys a power plant where the Mississippi and Missouri rivers meet near St. Louis. The flooding in the Upper Mississippi Valley in 1993 affected nine states and caused billion of dollars in damage. Photo Credit -NPR

Yes. Or, well, we tried.

In 2009, only sixteen years after the devastating 1993 flood, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) published the Upper Mississippi River Comprehensive Plan (commonly referred to as the Comp Plan) evaluating flood risk management alternatives in the region. The Corps looked at 14 federal project alternatives. Almost all of them combinations of raising or maintaining levees to 500-year and 100-year accreditations (before the 1993 flood, most of the levees in the region were 50-year accredited levees). A few alternatives looked at designated floodways to offset flood stage impacts, buying out entire levee districts, or relocating urban infrastructure in the floodplain.

But all of the alternatives took an all or nothing approach (everyone got 500-year levees or no one got any levees) and the evaluations lacked nuance. So it was no surprise that the Corps ultimately found that none of the alternatives had merit. In other words, 77% of the land protected by levees on the Upper Mississippi and Illinois Rivers is in agriculture – the vast majority row crops – and investing billions of dollars to protect corn and soybeans from major flood events just isn’t in the public interest.

In lieu of a path forward for the Upper Mississippi River, levee districts have been left to act individually to manage their own flood risks. How has that turned out? Not good.

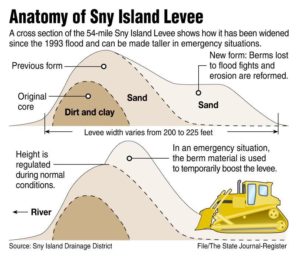

In 2014, the Sny Island Levee Drainage District, located in Illinois on the Mississippi River above the confluence of the Illinois River, submitted an application for 100-year flood accreditation to FEMA. During FEMA’s consultation with Corps and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, they discovered that the District had not been authorized to raise their levees to secure 100-year accreditation. Since the Sny levees are “federal projects” they need federal approval to make any modifications and any development in the floodplain requires permits from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

In 2014, the Sny Island Levee Drainage District, located in Illinois on the Mississippi River above the confluence of the Illinois River, submitted an application for 100-year flood accreditation to FEMA. During FEMA’s consultation with Corps and the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, they discovered that the District had not been authorized to raise their levees to secure 100-year accreditation. Since the Sny levees are “federal projects” they need federal approval to make any modifications and any development in the floodplain requires permits from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

In fact, the Sny Island Drainage District asked the Corps to raise their levees in 1996. The Corps declined and told them that while they could pursue the modifications at their own expense, it was unlikely their proposed project would secure the necessary environmental permits. The Sny claims that they received all the necessary approvals from the agencies, but so far, neither the Sny nor the agencies have been able to find any documentation to substantiate the claim.

Models completed by the Corps over the last year show that the actions of the Sny alone is causing the Mississippi River flood stage between Hannibal, MO and Lock and Dam 21 to increase by almost 4-feet under the worst case scenario. Illinois state law limits flood stage impacts at the worst case scenario to 0.1-feet in urban areas and 0.5-feet in rural areas.

And the Sny might not be the only levee district to take matters into their own hands. It’s likely that other levee districts have pursued similar levee modifications without the proper permits and approvals. This is very concerning for anyone living in the region as these rogue levee modifications could have flood stage implications as far south as St Louis.

The Upper Mississippi River is in desperate need of systemic flood risk management. But a true flood risk management plan requires all levels of government – local, state, and federal – to share the responsibility for keeping communities safe from flooding. It should minimize inappropriate and unnecessary use of the floodplain, exhaust all nonstructural approaches before turning to levees (which should be a last resort) and mitigate flood damages when they do occur. These concepts are not new. The answers to responsibly manage flood risk have been around for decades and one of the best guides to responsible floodplain management, “Sharing the Challenge: Floodplain Management in the 21st Century” was written in reaction to the disastrous 1993 Midwest Flood.

Instead of pursuing a similar Comp Plan process aimed at identifying structures the Corps can build, which was done in the 2000s, stakeholders on the Upper Mississippi River should pursue a Master Plan that follows sound floodplain management practices and does the following five things:

- Clarify the scope, vision, and goals for reducing flood risk along the UMR.

- Identify recommendations and activities that all levels of government, landowners, and stakeholders within the region can take to reduce flood risk. This should include specific short- and long-term activities to be implemented by all levels of government, communities, drainage districts, landowners and other entities.

- Establish a consultation and decision-making framework for landowners, drainage districts, municipalities, state and federal agencies, non-profit groups, and other stakeholders to effectively implement Master Plan goals and recommendations.

- Emphasize multiple-benefit and nature-based flood risk management approaches (like non-structural alternatives, wetland and floodplain protection and restoration, levee setbacks and removals, floodplain development restrictions, and similar measures) that provide multiple benefits of protection and restoration of ecosystems, improved water quality, as well as safe conveyance of flood waters and reduced flood stages

- Identify how to maintain and update data sets, surveys, and models to ensure the plan is being successfully implemented and guide the development of new recommendations and activities to address emerging issues.

At this point, it is unclear how this collaborative strategic planning will move forward. The Senate version of the Water Resources Development Act, S. 2848, contains a provision, Section 4010, to establish a new Upper Mississippi River flood risk management study. However, the process and product that would be authorized under Section 4010 seems disastrously similar to the failed Comp Plan. There are also rumors the Midwest Congressional delegation is working on language for the House bill, H.R. 5303. With the upcoming Mississippi River Commission meeting and interest expressed by Congress, it’s clear the Upper Miss is on the cusp of a new effort to find some systemic flood risk management solutions. And it’s never too early to start pushing for the widespread implementation of nature-based flood risk management solutions for the Upper Mississippi River.